Introduction

A common theme in the West is that married men and women are to be faithful to their wives and husbands, and those that are not are adulterers. Indeed, this interdict is one of the Ten Commandments: “Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery.” Sexuality and sex are part of a social and moral web that defines what it means to be a good person. When one surveys other societies one discovers that monogamy, and monogamous sex, is not the only moral model followed by human beings.

It is therefore of interest to sociologists that extramarital relationships are not an uncommon phenomenon in Vietnam, and that extramarital relationships in Vietnam mean something quite different from the Western understandings of such relationships. Unofficial statistics from health research (Family Health International, 2006; Elmer, 2001) have shown that approximately 70% of Vietnamese men have had extramarital relationships. Extramarital relationships are not a new trend either; they are, indeed, a deep cultural pattern: Vietnamese traditional folklore has many poems describing the relationship between a man and many women. For example:

Anh đâu phải mê bông quế

Mà bỏ phế cái bông lài

Quế thơm ban ngày, lài ngát ban đêm

I love the cinnamon flower

But I will not abandon jasmine

Cinnamon is fragrant in the daytime; jasmine, nighttime (E-cadao.com)

In Vietnam, the concept of extramarital relationships has a wide range of actions and meanings, from a man going to a masseuse, seeking a sex worker or party girl, to having a sweetheart or sweethearts, and even having a “second” wife. In fact, Vietnamese men are not likely to see most of these forms of extramarital relationship to be adulterous or an act of infidelity. As this research demonstrates, extramarital relationships in Vietnam are more

productively seen as a form of male privilege and a process of male identification and bonding than the result of a failed relationship between a husband and a wife.

Extramarital relationships are an important signifier of masculinity in Vietnam. In the past, having more than one wife indicated a man’s high status and wealth; at present, for many men and their male audiences, having sexual relationships with women other than wives indicates “maleness,” sexual potency, and prestige. Sociologically, extramarital affairs go beyond the dyadic relationship of a husband and wife. They are a phenomenon of men in groups: they are about male friends, business-relations, and colleagues, what each of these male cohorts think and admire, how men cover for each other and keep it secret from wives, and how men reproduce the masculine identification in one another. These male relationships, so tellingly reinforced in these reference groups, are an essential component of Vietnamese culture and its regulations about sexuality.

The communist regulation of sexuality banned polygamy in 1960. In communist theory and Vietnamese party practice, extramarital sexuality is considered a social evil, one not sustainable in a society that follows communist principles. It is no surprise, then, that the Vietnamese government has put the blame for extramarital affairs on Westernization and the impact of the free-market. The government has launched many campaigns against this “social evil.” Its efforts have little success because in reality, extramarital relationships are deeply embedded as cultural and social constructs of Vietnamese masculinity and male conformity. Men who do not have extramarital relationships can be understood, sociologically, to be “positive deviants” (Family Health International, 2006). Moreover, as Enloe points out, the construction of masculine ideals cannot be accomplished without constructing feminine ideals that are supportive and complementary, including the management of feminine respectability and feminine attractiveness (Enloe, 2004). Vietnamese men’s extramarital affairs are tolerated in Vietnamese society because respectable Vietnamese women are constructed as keepers of morality, and attractive Vietnamese women are supposed to be naïve and submissive in sexual relations.

Extramarital relationships are an essential component of Vietnamese masculinity. It is rooted in a patriarchal system that privileges men over women. Before the new law on marriage and family was passed in 1960, polygamy was legal, allowing a man to have many wives and concubines. Today men remain the head of the household, and son preference is still widely practiced. However, communist principles of gender equality combined with state-supported and rapid capitalist economic development are changing the position of women in Vietnamese society. More women are working out of the home and making equal or more money than their husbands and more women are educated and participate in politics. This has created stress on the traditional family as women begin to renegotiate the terms of family life, and men cling to the narrow definition of masculinity that privileges them. This traditional ideology of men being the breadwinners and the unquestioned head of the household is difficult to maintain in this new reality. Vietnamese men are feeling threatened by the economic, educational, and social progress of women. The consequences

may range from the renegotiation of the private and domestic gender roles in the family toward equity and mutual responsibility to the resurgence of traditional values and even more emphasis on sexuality as the means to control women and confirm masculinity.

This paper is based on survey field research and in-depth interviews. In this paper the concept of extramarital relationships is investigated toward understanding how it is culturally framed and enacted in Vietnam and in the broader context of the reproduction of masculinity and gender relations.

While not included in this paper, we placed our analysis within the structures of the traditional and contemporary Vietnamese family. It is ironic that, while family is identified as the most important factor in the life of the Vietnamese, men are spending more time away from their families with their male friends, and engaging in extramarital relationships. This can be understood by examining the traditional family, the clash between laws and norms, and the re-configuration of the contemporary family with regard to love, marriage, divorce, and the power between husband and wife in a marriage.

In this paper we explore the concept of extramarital relationships in its representations in traditional Vietnamese literature and folklore on male-female relations and polygamy, second, in the understanding of male and female sexuality through the use of gendered language in today’s time, and third, in the variety of extramarital relationship forms and Vietnamese men’s and women’s attitudes toward each form.

We conclude with an exploration of the reproduction of masculinity, using extramarital relationships as a significant variable, will show how extramarital relationships fit in the construction of Vietnamese masculinity and how male and female sexuality and identity are intimately connected to a web of relationships sustained by male participation in extramarital relationships.

Methods

This field research is based on face-to-face survey interviews and follow-up in-depth interviews in Vietnam.i Quota sampling was used for the survey to insure enough cases (around 50 or more) in the sub-categories of gender, educational level, regions, urban/rural areas, and economic conditions. Because of the emphasis on extramarital relationships of Vietnamese men, the quota for men was greater than the quota for women, the quota for married people was greater than the quota for single people, and the quota for people old enough to be married was greater than the quota for those who are too young or too old. The quotas for different regions were also different: 100 respondents in the North, 50 in the Middle, and 70 in the South. The reason was that the North is more than 4000 years old and is the core of traditional Vietnam, while the Middle and the South are much younger and less Vietnamized. The South had a larger quota than the Middle because it is physically bigger and is the economic heart of the nation. Since most Vietnamese are ethnically “Kinh” and theoretically do not practice religion, the quotas for ethnicity and religions have huge

differences between the Kinh and other ethnicities, and between no religion and other religions. Regarding quotas for economic conditions, five main big cities of Vietnam and the peripheral rural areas of each were the source of interviews. In addition, haphazard and snowball methods were used that provided introductions to respondent friends or colleagues. This method was used mainly to interview those who are state officials and upper-class because it was impossible to approach them without social connections.

Of all the 220 survey interviewees:

• Gender: 50 were women, 170 were men;

• Urban/rural: 74 were rural, 146 were urban

• Marital status: 42 were single, 174 were married, 3 were divorced, and 1 was a widow;

• Age: 28 were less than 26 years old, 77 were from 26 to 35 years old, 69 were from 36 to 45, 54 were from 46 to 60, and 2 were above 60;

• Religion: 38 were Buddhists, 13 were Catholics, 2 were Islamic, and 167 did not follow any religion;

• Ethnicity: 209 were Kinh, 3 were Khmer, 2 were Cham, 5 were Chinese, and 1 was Tay;

• Educational level: 64 did not finish high school, 80 finished high school, 69 had a college degree, and 6 had a higher degree than college;

• Economic condition: 10 were economically poor, 83 were fair, 105 were good, and 22 were excellent

Vietnamese Sex, Love, Marriage and Divorce

Love

In traditional marriage, the parings were arranged, and most couples did not know each other until the wedding night. Love was then assumed to develop between the spouses after marriage. Marriage for love hardly existed. However, this notion started to change in the early 20th century. By 1930s, romantic love was closely linked with a demand for public reforms by the intellectuals who grew up in the French education system and who saw traditions as obstructions to progress and development. They attacked the extended family and traditional marriage as the essence of traditional society and asked for a nuclear family and a marriage for love (Phan and Pham, 2003).

During the Vietnam War, love became a literary theme for many female writers in the South. Love was seen as an escape from the general feelings of despair, frustration, and disillusionment in war time. The topic of romantic love was very popular in Southern

literature. On the contrary, Northern writers remained silent on romantic love. They focused on the main theme of the struggle for a national revolution, socialist transformation, and the collectivization of the countryside. Many fictions also contained love stories, but they were bound up in the socialist ideology of altruism and self-sacrifice. Love was only true and lasting if people placed the interest of the nation above their own (Phan and Pham, 2003).

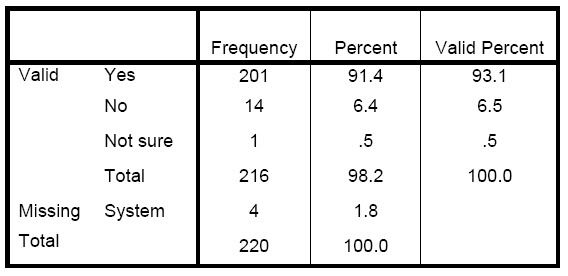

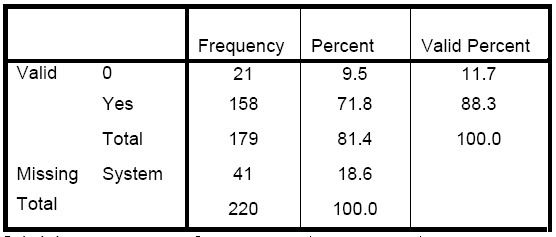

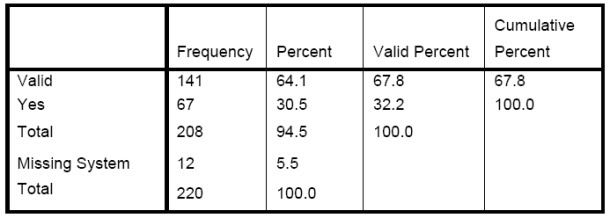

In the short period after the War, love was used to describe the impact of war on victims: war was the cause of lovers’ separations and sufferings. Love then became less abstract, and was depicted as a problem confronted by people in their everyday lives (Phan and Pham, 2003). If love was supposed to develop between the couple after marriage in the past, love and attraction now are the factors leading to marriage. 93.1% of respondents said that love is necessary for a good marriage (Table 1) and 88.3% said they got married on the condition of love (Table 2).

Table 1: Love is necessary for good marriage

Table 2: Reason for marriage: you loved him/her

Only 14 respondents in the survey said their marriages were arranged, and most of them were 40 years or older. Given the previous discussion on arranged marriage, the number 88.3% is too high to be reliable. However, it shows that Vietnamese people now strongly believe in the ideal of love for marriage. This is understandable because economic prosperity generates individualism and the desire of the self to be loved. Desire and love mirror the process of capitalism, accompanied by urbanization and consumption. Capitalism emphasizes the ability to choose and getting what one wants. Urbanization drives people out of their local settings, weakening the traditional sense of collectivity, and thus making

people more aware of the self. Love is, after all, the action of an individual (self) to pick and attract the person he/she wants.

The two views on love – love comes after marriage (traditional) and love precedes marriage (modern) – may be opposite but they share the same underlying message: a person can only find true happiness in a marriage (Phan and Pham, 2003).

Sex

Vietnamese people do not like to talk about sex, and not many write about sex either. In northern Vietnam, before the Renovation, almost no publications on sexuality existed. Only recently have books on sexuality begun to appear in bookstores nationwide (Khuat, 1998). But the government continues to impose a ban on explicit sexual images in cinema, television, and newspapers (Knodel et al., 2005). When Vietnamese people do discuss sex, they do it indirectly. Sexuality is referred as “that matter,” or the vagina and penis as “that thing.” They also use flowery language to talk about sex, most of which is related to food.

Because talking about sex is a taboo, sex is not included in the education, and parents are reluctant to discuss sex with their children, hoping they can find out on their own. Consequently, most young people get married without the least elementary knowledge about sex (Khuat, 1998). The question is then asked: whether or not Vietnamese people could find pleasure in having sex if they are so ignorant about it.

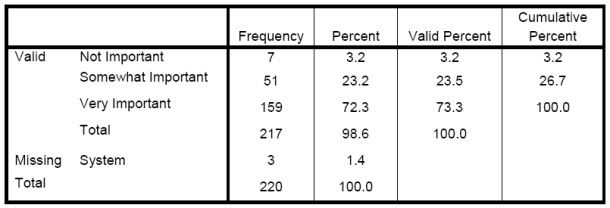

In an extensive study on sex and aging in North and South of Vietnam, Knodel et al. found out that “sexual activity shows little relationship to marital satisfaction and harmony” (Knodel et al., 2005, 17). This finding, along with the fact that men often go out to seek sexual pleasure from sex workers and sweethearts (Woffers et al., 2004 Elmer, 2001), suggests that sex and marriage may be separated. Yet, 73.3% of the respondents said it is very important to have a harmonious sex life with their spouses (Table 3). This could be explained by the more open attitude about sex, less emphasis on having children and more on intimacy between the couple, and the influence of Western culture.

Table 3: Harmonious sex life

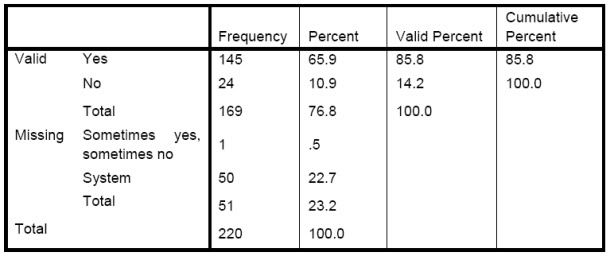

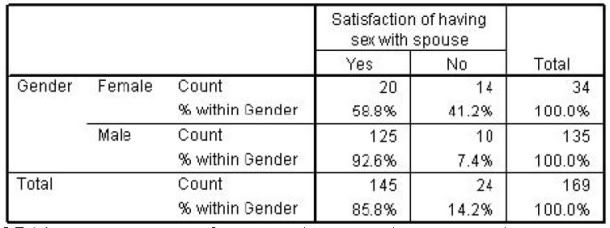

Table 4: Satisfaction of having sex with spouse

Table 5: Satisfaction of having sex with spouse across gender

85.8% of respondents reported being satisfied with their sex lives (Table 4). However, because sexuality is highly related to masculinity, it is no surprise that while 92% of male respondents said their sex lives are satisfactory, the corresponding number for females is only 58.8% (Table 5).

Marriage

Vietnam has a very high rate of marriage: in 2000, 66% of men and 62% of women older than 15 were married and only 3.3% of Vietnamese from 50 to 54 never got married (Le, 2004). Being single in Vietnam is socially stigmatized. For Vietnamese men, it means filial impiety. A man’s most important duty is to reproduce a son: “The Annamite loathes dying without being assured of male dependents” (Kherian, 1937 in Pastoetter) and “Male celibacy is always in complete disfavor. It continues to be considered as an act of filial impiety” (Nguyen Van Huyen, 1939 in Pastoetter). For women, being unmarried means that they do not perform their “natural vocation” of reproduction: “All women, wherever they are … all have the function of being pregnant and giving birth” (Tran Thi Que, in Rydstrom, 2004, 77). Being a mother is central to the definition of womanhood in Vietnam, and thus, a single woman is regarded as a failure, and surrounded by rumors of having a bad temper, selfishness, and sexual abnormality. Women who remain unmarried have to negotiate within the system to prove their femininity by having relationships with married men, acting as mothers for children around them such as nieces and nephews, or becoming the caregivers for their parents (Belanger, 2004). In general, people who are not married are

considered as unfulfilled, and become a target for constant marital matching. The story “Cho duyen” (Waiting for a Match) by Nguyen Thi Minh Ngoc revolves around unmarried sisters who are quite content with their lives and do not want to get married just for the sake of it. However, they had to change their minds in the end because that only getting marriage would make their parents happy. This implies that there are huge pressures from families and the society at large to make people get married.

Marriage also means adulthood in Vietnam. Only after getting married does one become a complete adult and gain social recognition (Belanger, 2004). Adulthood carries more significance in the society that is strictly based on the hierarchy of gender and age like Vietnam. The Vietnamese language could prove the importance of marriage. When asking about a person’s marital status, the question is not “ Are you married?” but “Have you married?” and the answer is not “Yes or No” but “ Already or Not yet” (Proschan, 1998 in Pastoetter)

But marriage has different meanings for Vietnamese men and women. Proschan argued that many Vietnamese men believe that women are perfectly happy with a companionate marriage, which involves sufficient zeal to produce offspring, but is not complicated by passionate desire (Proschan, 1998 in Pastoetter). This view of marriage is not very different to that of traditional marriage: “Marriage is for the Annamite a question of business and the procreation of descendants, rather than of sentimental love” (Jacobus X., 1898 in Pastoetter). That means that if men want a romantic relationship, they may search for it outside of marriage. For women, marriage is often depicted in fictions as disappointments and bitterness. Writers, most of them are female, focus on the failings of marriage, especially the loss of communication and intimacy between husband and wife. Many also write on the clash between romantic expectations and the mundane realities of everyday life. Romance becomes unstable within marriage which turns out to be an emotional deadlock. The consequences are women searching for love outside of marriage as well (Phan and Pham, 2003). However, the data shows that marital status hardly influences respondents’ beliefs about romance, faithfulness, and equality in the family. It can be said that marriage for the Vietnamese is a duty. Being married brings a person social recognition as well as avoiding the stigmas associated with celibacy. However, marriage is also a dilemma. While men think that the most important thing about marriage is reproduction and may go outside of marriage for emotional as well as sexual satisfaction, women are beginning to demand romantic love in marriage. The consequence is love is sought outside of marriage. Given the social stringencies on women’s morality and conduct, fewer women commit adultery than men. Unhappy married women then have three choices, 1) put up with the marriage and do like their counterparts in the old time did: “On her side, the woman has not generally a very great affection for her husband, but concentrates all her love on her children” (Jacobus X., 1898 in Pastoetter), 2) involve in extramarital affairs, or 3) file for a divorce. All the three choices have fewer disadvantages for the man than the woman. A woman has to tolerate a marriage without love, or she seeks love in extramarital affairs,

which might be illusionary, and for which she will face great social blame, or she suffers from financial and emotional losses of a divorce.

Under industrialization, marriage has become commercialized. Marriage services exist in many forms, including online dating sites, blind dating services through national newspapers (such as the Lao Dong Newspaper), and matchmaking companies that help foreigners, in particular the Korean and Taiwanese, to marry Vietnamese women. Young Vietnamese are also very concerned with the financial ability of their partners, rejecting the old notion of “one cottage and two golden hearts” (mot tup leu tranh, hai trai tim vang). More than half of the respondents also stated that it is very important for the family happiness to have good economic conditions.

Divorce

Divorce in Vietnam is increasing from 22,000 cases in 1991 (Le, 2004) to 86,152 cases in 2005 (Statistics from the National Court of Vietnam), and domestic violence accounts for the highest number of divorce cases, followed by adultery (Statistics from the National Court). There are several reasons for the increasing divorce rate, such as the liberalization of divorce laws, more open public opinions, the improved status of women in education and work, and higher expectations of marital bonds between husband and wife (Pham, 1999). Interestingly enough, not only are women expecting more of their men (because they are more educated and economically independent), men are also demanding higher qualities of their wives such as appearance, social skills, and charm due to the elimination of legal polygamy.

The 1986 Law on Family and Marriage includes a long chapter on divorce law. Both men and women now can initiate a divorce, but the process makes it hard to do. There is no “no-fault” divorce, and couples must prove that they have serious problems and that they have tried hard to reconcile their difference before a divorce is granted. Moreover, a divorce is more likely made possible if both parties seek an end to their marriage. If only one party wants to have a divorce, the court tends to require a continuation of reconciliation before hearing the case again (Wisensale, 1999).

Even though Vietnamese women now have equal rights to seek a divorce as men, it is less common for a woman to get a divorce, especially after having children. First, Vietnamese women still strongly believe that divorce is always bad for the children. In addition, many women may not be financially independent enough to raise their children. Divorced women also have more difficulty remarrying than divorced men.

Marital and Extramarital Relationships in Language

Ca dao is a special form of traditional literature in Vietnam. Ca dao, loosely translated as unaccompanied song, is the genre used by peasants using Vietnamese language in contrast to the poems in Classical Chinese by scholars and the mandarins which were inaccessible to the majority of Vietnamese who could not read Chinese. Ca dao was orally

transmitted and dates back more than a thousand years ago. Because ca dao remained outside the purview of feudal governments, it was a truthful source of everyday life and revealed concerns of ordinary Vietnamese. Therefore, ca dao was candid about many topics that were highly regulated by Confucianism, such as arranged marriage, polygamy, concubines, wives complaining about husbands and mother-in-laws, and conjugal infidelity.

Under feudalism, for hundreds of years polygamy was legal, but only the man was allowed to have many wives:

Sông bao nhiêu nước cũng vừa,

Trai bao nhiêu vợ cũng chưa bằng lòng[1] (e-cadao.com)

The river could receive endless water

The man could never be pleased no matter how many wives he has

Having many wives in a traditional family was important because they were the main laborers:

Ai bì anh có tiền bồ

Anh đi anh lấy sáu cô một lần

Cô Hai buôn tảo bán tần,

Cô Ba đòi nợ chỗ gần chỗ xa,

Cô Tư dọn dẹp trong nhà,

Cô Năm sắc thuốc mẹ già cô trông

Cô Sáu trải chiếu giăng mùng,

Một mình cô Bảy nằm chung với chồng (from e-cadao.com)

I have a basket of money

I marry six wives at the same time

The first does the family business

The second collects the debts

The third cleans the house

The fourth takes care of my mother

The fifth makes the bed for me

Only the sixth sleeps with me

The wife was supposed to be completely faithful to her husband:

Chờ chàng tháng tám đã qua

Tháng mười đã lụn tháng ba mãn rồi

Chờ chàng xuân mãn hè qua

Bông lan đã nở, sao mà vắng tin (from e-cadao.com).

I have been waiting for you for more than 8 months

October has passed, March went by

Waiting for you from Spring to Summer

The magnolia has blossomed; why I have not heard from you?

Faithful as she was, she was not allowed to be jealous if her husband had a sweetheart.

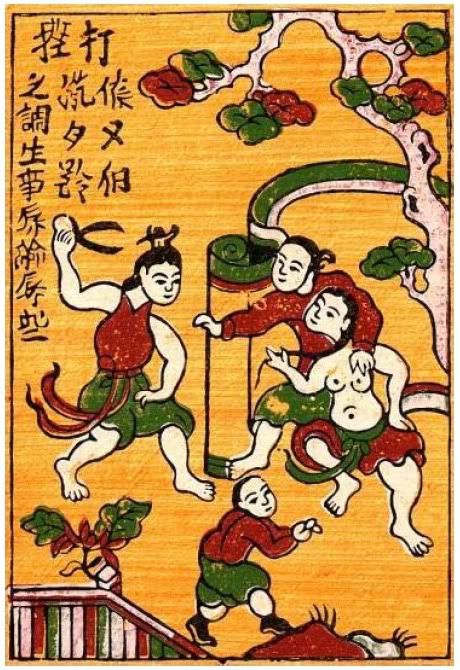

This traditional Dong Ho wood block print, over 500 years old, tells the story with this accompanying text:

The wife says to the husband’s sweetheart:

“Măng non nấu với gà đồng Thử chơi một trận xem chồng về ai”

You’re the bamboo shoot [young]; I’m a field hen [old and experienced] Let’s fight and see who’ll win him.

The son says to his mother:

“Mẹ về tắm mát nghỉ ngơi Ham thanh chuộng lạ mặc thầy tôi với dì”

Mom, let’s go home and take a rest If Dad wants adventures, let him be.

The husband says to his wife:

“Thôi thôi nuốt giận làm lành Chi điều sinh sự nhục mình nhục ta”

My dear, let’s calm down You make a fuss out of this, we all will be embarrassed.

Note the emphasis on permitting the husband to have his extramarital relationship, affirmed by the young son as merely an adventure, and expressed by the husband who exhorts his wife that her jealousy is an embarrassment (not his behavior) and will dishonor the family. A reading of a husband’s extramarital behavior is not anachronistic even today. Vietnamese wives must endure, and when she is confronted with her husband’s extramarital relationships, whether it is a sex worker or sweetheart, she may look inward to understand her “failure” rather than demand that he terminate his extramarital relationships.

The regularity in ca dao proves that the relationships between a man and several women is not a new phenomenon but has roots in Vietnamese tradition. Today, even though polygamy and prostitution are illegal, extramarital relationships are common and the language about sexuality and extramarital relationships is rich and can be divided into several categories: food, animals, and even family.

Food Analogies and Metaphors

The Vietnamese refer to the wife as “rice,” the staple they eat everyday, and the sweetheart as “noodle,” another form of rice but fancier, that the Vietnamese have often but not daily. The concept is filled with imagery:

“A husband eats rice for breakfast, noodle for lunch, and returns home for rice at dinner.”

Or more elaborately:

The husband takes his “rice” (wife) to have noodle for breakfast, take his “noodle” (sweetheart) to have rice for lunch. In the evening, “rice” returns to rice’s home, and noodle returns to noodle’s home; the husband eats rice but thinks of noodle.

The wife is also sometimes called “com nguoi,” the rice left over from the previous meal that is old and is no longer delicious, and premarital sex is described as eating the rice before the dinner gong is beaten (an com truoc keng). Similar to “rice and noodle” (com pho), but used mainly in the South is “nem” and “cha.” One male respondent explained that nem and cha, one a roll, the other a pancake, have different tastes but both are made from pork. Because nem refers to a woman other than the wife, the man’s relationship with her could be described as “meaty nem” (nem man) if sexuality is involved, and “vegetarian nem” (nem chay) if it is not. Understood in the context of Buddhism, vegetarianism is related to the diet of monks, men who do not eat meat and do not have sex. Vegetarian nem is most stereotyped as, though not limited to, a relationship between a man and a woman working at the same office, and both are sharing emotional intimacy. These emotional liaisons are threatening to the marriage because vegetarian nem can later turn into meaty nem, and the woman could become a sweetheart. Going to sex workers, for most Vietnamese men, only means a kind of service, and they call it “if you eat the cake, you pay for the cake” (an banh tra tien). These relationships are absent of emotional intimacy. Finally, if one is engaged in an extramarital relationship, one is said to “eat on the sly” (an vung).

The Vietnamese have a whole metaphorical field of food to talk about the relationship between a man and many women. The food analogies go hand in hand with how women talk about their relationships with men. They often use slang such as to catch a fish, to go hunting, or to trap. Because the men like to eat, the women give baits to trap, to hunt, or to catch men. The language shows the naturalization process of the men as the eaters and the women as the feeders.

Animal Analogies and Metaphors

In addition to food, Vietnamese men and women associate themselves with animals. Many Vietnamese men assume that they have the “blood of the goat” (mau de), an animal that is believed to be hyperactive sexually. It is no surprise that they drink wine mixed with goat blood and eat goat testicles to increase their sexual ability. If a man is being cheated on by his wife, he is a cuckold or he is wearing the horn (cam sung). The wife after having children is an old sow (lon se) whose breasts become unappealingly flabby.

Extramarital relationships are expressed as “chasing the bird, catching the butterfly” (duoi chim bat buom), “the bee and the butterfly” (ong buom), which indicates the bee and the butterfly as the wife and the other women, or “the cat eats fat” (meo mo) implying one cannot say no to an attractive person just as the cat never says no to fat. Vietnamese men

also say that they expect, after several years of marriage, “the cat wants fresh fish with which to play.”

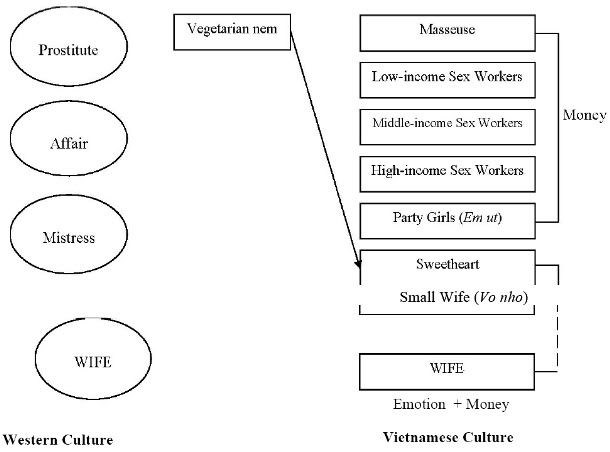

Forms and Hierarchies of Extramarital Relationships

The concept of extramarital relationship is divided into sex and non-sex relationships and has a wide range of meanings. The meanings in the sex relationships create a hierarchy: at the bottom of that hierarchy may be having manual or oral sex with the masseuse (many Vietnamese men do not consider this an extramarital sex), followed by seeking sexual liaisons, which have three levels: (1) low-income sex workers who work on the street, (2) middle-income sex workers in small restaurants, hair salons, clubs, cafes, and (3) high-income sex workers in discotheques, night clubs, and other expensive entertainment venues (Rekart, 2001). This is followed by the party girl who is a young and attractive “girlfriend” who has no commitment and easily leaves one man for another man, depending on who spends more money on her. The next levels involve emotional attachment: a sweetheart or a “second” wife.

In Vietnamese language, a party girl is called “em ut,” translated as the youngest sister in the family who is young and often gets a lot of attention and money from older people; and a “second” wife is called “small wife” (vo nho/vo be) which indicates a strong relationship and commitment that is slightly less than that with a (big) wife. In Western[2] culture, there are normally four main categories: the wife, the mistress, the affair, and the prostitute. It thus significantly ruptures the boundary for a man to engage in an extramarital relationship, i.e. moving from category of wife to mistress, affair, or prostitute. However, in Vietnam extramarital relationships have a hierarchal and categorical structure so that moving from one category to another does not create such a great rupture.

NON-SEX SEX

As the chart shows, the categories of extramarital relationships could be considered consumption categories, and they also mirror the process of industrialization and globalization that creates a class-based society. In the class-based system, the masseuse is at the bottom and the small wife is at the top. As the category goes up, the monetary investment increases, and so does the emotional attachment and responsibility expected from the man. When a man has a sweetheart or a small wife, he is also having the status of a boyfriend or a husband, and the role of a provider. That is why having a sweetheart or a small wife entails both money and responsibility. The class system and its connection with industrialization also mean that some of the categories of extramarital relationships did not exit in the past (such as masseuse, party girl, and small wife) and in rural areas (such as the differentiation of sex workers into low-income, middle-income, and high-income).

Masseuse

Vietnamese men rarely go to a massage parlor alone; they go in groups with other men. At the most basic level, men go together as buddies for entertainment or they go with business colleagues (both domestic and foreign), using this opportunity (and the female) as an exchange for the business. When Vietnamese men go to the masseuse they have two options: either having manual or oral sex right in the massage room or going somewhere else to have sex with the masseuse. Most Vietnamese men do not consider manual or oral sex by the masseuse a form of sex, and therefore, it is not regarded as an extramarital relationship.

Sex Workers/Prostitution

Prostitution has a long history in Vietnam. It was very common in the 19th century, and sex workers were classified into the Annamite “Bamboo,” the Chinese brothel, the “Flower boats,” the Annamite “Daylight whore,” and the Annamite “Mistress of the European” (Jacobus X in Pastoetter). In 1935, 4,000 people were estimated to be working in the sex industry, not including geishas and dancers (Khuat, 1998). The policy of the French colony at that time was regulation through registration and supervision of prostitutes and safeguarding women from being deceived into prostitution. In 1954, before the North was liberated, there were 12,000 professional sex workers in Hanoi, of whom 6,000 were licensed. After the Communist Party took over the North and later passed the law on Marriage and Family making prostitution illegal, prostitution was claimed to be eliminated. However, about 300 to 400 people were caught every year working as sex workers. At the same time, in the South, statistics from the Ministry of Society of the Saigon government showed that there were 200,000 sex workers prior to 1975. Many of these sex workers provided their services to American soldiers during the Vietnam War as a part of the “Rest and Recreation” agreement between the US and South Vietnam (Pastoetter). After the country was united, the government shut down prostitution houses and sent sex workers to reeducation centers. Within 10 years, the government claimed that prostitution was eliminated in the South (Pastoetter).

In effect, reports revealed that the sex industry made a resurgence in Vietnam in the 1980s (Quy, L.T. in McNally, 2003). It operates in “a relatively open manner [and is] practiced in almost all hotels, inns, restaurants, dancing halls, beauty and massage parlors, public parks, street pavement, bus stations, railway stations, and any other places such as a dyke embankment or sea beach” (Quy, L.T. in McNally, 2003, p.112). This long list itself shows how common and visible prostitution has become in Vietnam as compared with being invisible and theoretically eradicated before the Renovation. According to the Department of Criminal Police, Ministry of the Interior, in the first six months of 1990 Vietnam had 40,000 sex workers (Pastoetter). Unofficial statistics from Khuat claimed that there may have been half a million sex workers in Vietnam prior to 1998. Studies suggest that as transportation and construction happen rapidly, there is more demand for sex because more people are highly mobile in their business (Elmer, 2001). Commercial sex begins to mushroom along highways and major transportation routes (Beesey in Elmer, 2001), as well as around bus stations (Family Health International in Elmer, 2001).

Clients of the sex industry include all social classes, including workers, truck drivers, students, engineers, and government officials, to name a few. Clients regularly start off drinking beer and then seek prostitutes after that.

Sex workers themselves are very young, ranging from 18 to 30 years old, most of whom are low educated and from rural areas (Elmer, 2001). Few opportunities for jobs and lowwaged jobs are one reason for these young women to go to cities involved in the sex industry (Pastoetter). On average, a sex worker’s income is seven times higher than the average income of the population of the Red Delta River (Khuat, 1998). But poverty is not the only reason. Family conflicts and feelings of hopelessness about husbands and boyfriends also force these young women into being sex workers (Pastoetter). Many of them are from overcrowded homes, or suffer from domestic violence, abuse, and abandonment by husbands or boyfriends (Elmer, 2001).

According to Rekart (2001), sex workers are divided into three groups. Low-income sex workers work on the street and call themselves “street waiters.” These sex workers offer oral sex, quick sex (less than half an hour), one-hour sex, and over-night sex. Middle-income sex workers work at places such as “hugging” cafés (cafés om), small restaurants, and beauty salons. Middle-income sex workers are less likely to be arrested than street sex workers, and even if they are arrested, the venue owners will pay to get them released. High-income sex workers work in discotheques, karaoke bars, and night clubs. They are the most beautiful and educated. Many of them can speak foreign languages with foreign clients. They reserved private rooms in the hotels or karaoke bars. Some of them work as “contracted wives” or “temporary wives” to businessmen who have to be away from families for quite a long time. Many private companies provide the contemporary wife service with around 20 to 30 women as workers.

In the wake of the booming sex industry, in 1995 the government passed a decree labeled 87/CP aimed at “social evils” of which prostitution was one attacking target (McNally, Marr and Rosen, Walters, and Pastoetter). Prostitution was seen by the State as a threat to the ideal socialist family and became a metaphor for many other problems facing a more open Vietnam after Renovation (McNally, 2001). Family was to blame, “Carried away in moneymaking, families have reduced their important roles in education” (Nguyen Thi Hue in McNally, 117), but was also seen as the resolution to this “moral panic”: “It is our view that we need to do much more to strengthen the traditional values in the family relationships and increase the role of the community in the monitoring and surveillance of ethical actions of each individual” (Quy, L. T. in McNally, 114). Laws relating to HIV and prostitution were drawn closely with the aim to strengthen family, the basic cell of the society, which would protect the country from the external threat. According to Vu Trong Thieu, a member of the AIDS Prevention Committee of the Ministry of Culture and Information, “The question of ‘family’ and ‘family’ culture should be taken into account in AIDS prevention activities” (McNally, 117). The State came up with a new type of family, the “cultural family,” and the criteria to achieve this title are, in Vu’s opinion, practicing family planning, leading a progressive and happy life, and maintaining good relationships with the neighbors (McNally). While the family is expected to educate children about morality, it is also the family that is known to sell daughters to middle agents to be prostitutes (Kelly and Le in Wolffers et al., 2004). Without real financial support from the

state, it is hard for the family to achieve the vision of a cultural family, and even harder to act as a protector against “social evils.”

The State’s efforts to eradicate the sex industry failed. The first reason is many state officials are regular clients of the sex industry. According to data from police records between 1995 and 1998, state officials accounted for two thirds of known clients (Deutsche Presse-Agentur in McNally). Commercial sex is a large part of Vietnam’s growing leisure industry. When there are so few options for leisure, drinking beer and seeking sex workers offer relaxation, enjoyment and even adventure for men who begin to have money to spend on themselves, friends, and colleagues (McNally).

Moreover, the sex industry is an important source of income because sex workers “generate a lot of indirect employment” (Colimoro in Walters, 2004, 87). According to Walters, sex workers send money home to families, supporting their parents, siblings, and relatives, fulfilling their roles as dutiful daughters. Go-betweens, middlepersons, minders, and pimps assist sex workers by providing transportation, contacts, and arrangements, and get a share for their services. Hotels, clubs, bars, cafes, hostels, etc. have their income from room rents, drinks, and services. For example, Walters noticed that the girls are trained to order plenty of drinks. The police and authorities also have their benefits. Sex workers pay the police to be allowed to work without fear of arrest or harassment. Hotels, clubs, and bars pay the police in order not to be raided. They also have to pay everyone in the system such as heads of the District or Ward, the health inspector, tax collectors, tourism companies, fire people, so on and so forth. Walters estimated that a policeman may earn US $42,000 a year, equivalent to the income of a very wealthy person in Vietnam. If the police shut down the prostitution houses all these people would have very little money, and all of them, including sex workers, would suffer (Walters, 2004). Thus the government of Vietnam has been caught between the state’s vision of an equal and socialist society and the informal support of the sex industry from state authorities.

The clients of the sex industry include people of all education level, social classes, and marital status. In fact, education level and marital status have no significant impact on whether a man frequents sex workers or not. The social classes decide the kinds of sex workers one frequents and the frequency. A man, who is poor and cannot afford a sex worker on his own, pools the money with other men and shares sex workers. Richer men may pay for higher-class sex workers and frequent them more often. The occupation also affects if and how often men seek sex workers. Tourist guides, drivers, and businessmen who often go on the road are more likely to be clients of the sex industry. Moreover, these jobs allow people to make fresh money that is out of the calculation, making it easier to spend and hide this money from the wife.

Many Vietnamese men regard men going to sex workers as an entertaining pastime and not a moral issue. It is a regular and integral part of male friendships and a critical lubricant in the business nexus. As long as their wives do not know, and they still love and be “responsible” for their families, it is acceptable. However, when a woman has an extramarital relationship she is condemned as morally depraved. Men consider sexual activity as a way to satisfy men’s stronger needs than women’s, as well as to reinforce their masculinity and to bond with other men.

Given the significant dependence on the sex industry (sex workers and people involved need it for money, men need it as an expression of masculinity and a form of masculine exchange), and the social acceptance of men visiting sex workers, it is impossible for the state to eradicate or reduce the size of the sex industry for the time being.

Scholars have criticized the state policy in handling prostitution (McNally, Wolffers, Kelly, and Van Der Kwaak). Female sex workers rather than the male clients are constructed as a threat and are sent to reeducation centers. Moreover, female representations from calendars manufactured by state companies, advertisements for tobacco and alcohol in restaurants, to state-sponsored beauty contests and anti-social-evil posters send the message that women’s bodies are considered sexual, available, promiscuous, and aplenty for male enjoyment (McNally).

Statistics have shown that many men seeking prostitutes are married. In a study of STD male patients by the Pasteur Institute, 73% of the patients visited sex workers within the last three years, and married men were found to visit sex workers as often as single men (Thuy et al, 1999 in Elmer). The excuses were being away from home on business, unhappy marriages, psychological stress, or a way to relax (Elmer). Prostitutes, along with sweethearts, may functionally have become a substitution for outlawed polygamy. Many men choose prostitution because it gives them access to more than one partner without any emotional and financial commitment and responsibility. Studies also confirm a widely-held belief that men cannot say “no” in situations of male pressure like drinking beer at the restaurants and seeking sex services afterwards, that they lack personal control over their sexuality, and that patronizing sex workers is an “essential male cultural characteristic,” together with smoking, drinking, and gambling (Khuat, 1998; and Beesey, 1998 in Elmer). This ideology operates based on a double standard: proper women are supposed to be submissive and naïve in sexual issues, which gives men the reason to go to sex workers because sex workers can help them enjoy sex more fully. The sex industry is available and accessible for men of all classes, but women are not supposed to be aware of this industry (Woffers et al.). In fact, women do know that their husbands visit sex workers, and they discuss this issue within their women networks behind the men’s backs. Many women will respond by strictly controlling the incomes of their husbands to make sure that even if they may lose their husbands, their families, including their children and themselves, are not affected, at least financially.

Party Girl (Em ut)

“Em ut” is the category that is used for a young beautiful girl who is, in the hierarchy, either a high-class sex worker or a playing girlfriend. Men know that they are buying love, that they could not expect any commitment from an “em ut” and that an “em ut” expects only money from them. The relationship with an “em ut” is usually short, and one man can have several “em ut”s at the same time. An “em ut” is suitable for men who can afford and do not like commitment:

“I do not like living with another woman. I just want to meet several times a week or month, have sex, and then go out together.” (Male, 29, Ho Chi Minh City)

This suggests that “em ut” is the middle category between prostitution, which implies money only, and sweetheart or small wife, which implies more money but also emotional attachment. If an “em ut” has relationships with many men, she can be considered a high-class sex worker, and if she gets emotionally attached to a man, she moves from being an “em ut” to a sweetheart, or possibly a small wife later.

Sweetheart and Small Wife

Having a sweetheart or a small wife means a prolonged relationship and commitment not only emotionally but also financially, and sometimes includes having children. Because of this, sweethearts and small wives, unlike sex workers who are considered no threat to family happiness because it is just a kind of service, are likely to affect the family badly. When a man has a sweetheart or a small wife, he definitely enters the realm of “infidelity,” even in the Vietnamese context. The sweetheart or the small wife is assumed to take the husband away from his wife and children. It also means taking away the husband’s love, responsibilities, and money from the family. While many Vietnamese women think of husbands going to sex workers as fun, “biologically” natural, and harmless, most Vietnamese regard relationships with sweethearts or small wives as a danger.

Sweethearts and small wives are also far less common than sex workers because of the danger and financial and emotional commitment. They are expected to give men what their wives could not provide, such as indulgence, full attention, and no criticism. Men often claim that their sweethearts or small wives, not their wives, are their soul mates.

Many Vietnamese tend to think that when one has a sweetheart or a small wife, it is not for fun or showing off but because the relationship between the husband and the wife has become very bad or because the wife could not give the husband a son. Therefore, the irony is that even though having a sweetheart or a small wife means being infidelous, most men get sympathy from people who think of their affairs as an exit from unhappy marriages when divorce is still a taboo. Sometimes, men choose to have sweethearts or small wives over sex workers and “em ut”s despite the economic and emotional commitment because it means less risk of exposure. The interviews reveal that while a man’s friends knows that he has visited sex workers, very few know that he has a sweetheart or small wife.

The Phenomenon of Extramarital Relationships

While only 18.2% of respondents in the interviews said that they have had extramarital relationships, 92% said they knew people who have had extramarital relationships. This suggests that many respondents were probably not being honest and that extramarital relationships are common for Vietnamese men. In fact, extramarital relationships are common enough to make most people believe that they are acceptable. There are always available partners, both male and female, for men whose wives “fail to provide proper attention and stimulation” (Khuat, 1998). Several factors contribute to this phenomenon. The first one is that an extramarital relationship is an alternative to the traditional polygamy. When polygamy was legal there was a clear path to taking an additional wife. As Le Thi states:

With polygamy there is no registration of marriage as such. Marriages are not legally recognized by the state…If a wife is childless, her husband gives himself the right to take a new wife. His family openly expresses the wish for this and his wife has no alternative but to comply with and accept it or to divorce. In contrast, if the husband is childless, his wife has but to endure (Barry, 1966, 67).

This understanding and pattern persists in modern Vietnam, socially permissible although now illegal. If a man is not happy with his wife, and he is not allowed to legally take a concubine or second wife, he may seek a sweetheart.

Second, the sleeping arrangement where parents sleep in the same room as their children continues to exist, especially in rural areas (Pham, 1999). The geography of sleeping prevents married couples from having much intimacy such as sexual intercourse. Moreover, many Vietnamese women are too tired from working two jobs (outside of home work and domestic work) to enjoy having sex.

Third, economic prosperity enables men with disposable income to spend it satisfying personal pleasures including having a sweetheart or sex worker. However, since the relationship of one man with many women is not new in Vietnam and is essentially an agrarian and feudal construction, the main reason may be embedded in cultural ideologies about men and women: extramarital relationships are tolerable due to the ancient construction of masculinity and femininity with relation to sexuality.

The Construction of Vietnamese Femininity

Vietnamese women are constructed as the morality keepers. The strongly-held Vietnamese belief of “Phuc Duc” (Merit and virtue) works against the interest of women. “Phuc Duc” is a kind of karma concept which states that the merits one gains can pass on to succeeding generations, born and unborn. The Vietnamese believes that “Phuc duc tai mau” (Merit and virtue are caused by the mother): a good woman of proper conduct and ethics can bring happiness and good fortune to her family, and a bad woman brings tragedy and despair. Men, not restricted by this belief, are freer and not judged if they engage in bad conduct such as drinking, gambling, or cheating. When being asked whether they were angry when finding out their spouses had had sweethearts, 48.2% of male respondents said yes because it means their wives were unethical, while only 38% of female respondents said the same thing of their husbands. The gap between male and female respondents if their spouses had sought sex workers is bigger: 54.7% versus 34%. Women as the morality keepers were also used as by men to excuse venturing outside of marriage: many male respondents said if the women with whom they hoped to have extramarital relationships said no, then they (the men) would not have engaged in extramarital relationships.

Second, there is a double standard regarding sexuality for men and women. Women only are expected to remain a virgin until marriage. According to Go et al (2002), when questions on premarital sex were posed, immediately and only the consequences to the women are discussed. The omission of men in these discussions suggests two possible options: 1) The Vietnamese have an underlying assumption that men are inherently sexual and therefore premarital sex for them was socially acceptable or 2) A Vietnamese woman is considered as property that needs to be protected before being given to the owner – the husband. Most women and men believed that a woman should not have premarital sex in order to maintain the respect of their boyfriend, future husband, and husband’s family. The double standard, in Pham’s criticism, means that women’s sexuality is supposed to only serve the men. Respondents, male and female alike, believed that women, unlike men, have few sexual desires and are able to restrain their sexual desires, and therefore, should not have extramarital relationships. Good girls are supposed to be naïve, submissive, and passive in sexual relationships. This belief in “biological” differences between men and women may stem from the restriction on women sexuality under feudalism. It gets reinforced by the socialist government, in which women are to follow the socialist image of a worker, fighter, and mother. The image of a wife as a sexual object is relatively new. This belief also masks the cultural construction of femininity and naturalizes the cultural construction as natural: the Vietnamese do not want the women to have much sex, so they attribute that Vietnamese women naturally have low sex drives.

Third, Vietnamese women are family-oriented and family-bound. The Vietnamese believe that women cannot find happiness outside of marriage. Once in a marriage, the wife is the main caregiver who is responsible for family happiness and healthiness. Because the role of the woman in the family is so important, she is not allowed to have extramarital relationships and must make her family a priority.

“It is said that a man in the family is like the roof of a house and the woman is like the shoulder strap to raise the roof. A house has one roof but many shoulder straps. The woman has to take care of many tasks. If a woman has a love affair, she might not have time for her duty to look after the children so her sins would be considered more serious than a man’s. When a man has a love affair, it does not matter since his children are being taken care of by his wife. That is why, for a long history, men have been offered more lenient consequences for the same situation. (A man in Go et al’s research)

In the national contest “Vietnamese women of the 21st century” launched by the National Television Network to exemplify the “model” of a modern Vietnamese woman, one of the criteria is “a woman has a career but her family is still the base” or “being successful in social work but still manages the family well.” This criterion reinforces the double burden Vietnamese women have been shouldering (domestic unpaid work and paid work), and makes the family most important for Vietnamese women. It is no wonder that a female respondent could articulate the role of Vietnamese women so clearly:

• Vietnamese women must first be faithful. Sacrifice is most important for Vietnamese women, because only through sacrificing themselves can they remain faithful and nice. Many men were grateful for getting married to Northern Vietnamese women because their sacrifice kept the families stable and happy.

• Vietnamese women have to be hard-working and able to endure difficulties, which would help them overcome any hardships they have in life.

• Vietnamese women have to be able to take care of everything. They must know how to multi-task because beside their work, they have to shoulder their families.

• Vietnamese women have to “doi noi” (manage inside the house) as well as “doi ngoai” (manage outside the house which include dealing with the society in general and extended family members).

• Vietnamese women must be willing to learn to improve themselves, constantly trying to be better.

Notable in this description is the awareness of regional differences. It is widely believed that the Southern people are more corrupted by the West because of colonial history and economic development, and that Southern women do not have as many traditional values as those in the North. However, the statistics on gender ideologies (chapter 3) have proved the opposite: Southern people turn out to be more traditional than the rest of the country.

The construction of women as family keepers has prevented women from having extramarital relationships. In the survey 93% of male respondents believed that their spouses have been completely faithful to them; however the corresponding number for female respondents is only 61.1%.

In response to the high likelihood of their husbands having extramarital relationships, female respondents said that they keep a secret savings as a buffer against the husbands’ indiscretion because women are still held responsible for family financial management and the welfare of the children (Fahey, 1998 in Pastoetter). When women cheat on their men, however, it is socially unacceptable. Twenty point five percent and 26.8% of respondents cited social norms as the reasons why they think it is not acceptable for the women to have sweethearts or seek sex workers. Moreover, one respondent thought that no women ever has sweethearts and 12 thought the same of women seeking sex workers.

Contemporary literature reinforces Vietnamese women’s attachment to the family. It is depicted in Vietnamese short stories that women’s search for love would end in disillusionment first because even though men talk about love, their love extends only as far as the bedroom, and second, happiness in extramarital affairs are illusions, not the solutions to marital problems. In the end, those who venture outside of marriage for romantic love in these stories would come back and resume their roles as husbands and wives. The society at large still assumes that women can only find happiness within their marriage, not outside of it, and romantic love becomes the key for women to “reach the external paradise of marriage” (Phan and Pham, 2003).

However, as more women become independent and educated, many of them choose not to follow the rules imposed on them. As Hirschman claims, instead of loyalty, one has other alternatives: exit the system or voice their discontent (Hirschman, 1970). More and more Vietnamese women are getting married to foreigners, particularly Taiwanese and Korean. They choose to exit because

“Is it possible in this economic-driven time to still believe in “one cottage and two golden hearts”? If I stay home and marry a farmer who says he loves me but gambles, and drinks all day, makes one but spends ten, would I be happy?”

(Female, 23, Ho Chi Minh City)

These women are being widely criticized for going after money. In fact, they are being attacked for their disloyalty and lack of nationalism and authenticity (they choose materialism over love), and for the insult to Vietnamese masculinity (Vietnamese men feel ashamed and angry for not being able to “protect” their women). Other women exit by choosing not to marry and be confined in all the family obligations. Those who do not exit voice their discontent. Many female writers have begun to challenge whether or not marriage really brings happiness to the women by writing on the bitterness and disappointment in marriage and its consequences on women, both married and unmarried (Phan and Pham, 2003) (Yet, these authors do not know what the way out is for their female protagonists). Others, such as the famous director Le Hoang, publicly support women getting married to Taiwanese men and criticize Vietnamese men’s behaviors:

“It is true that before judging a woman, the men have to judge themselves first, and 1000 times more seriously. I go to the countryside many times, and I am very frightened to see that at 5, 6 pm, most of the men go drinking. I see them going along the streets and singing as they are drunk. If I were a woman marrying such a man and had to tell myself that I was happy because I married a Vietnamese man, that would be impossible for me” (Le, 2003).

At the same time, the Women’s Union, government institutions, and international organizations have been funding research on research on gender, particularly on marital relationships, family, and prostitutions, to name a few. These efforts to reshape masculinity and femininity would in the long run help create changes in gender relationships.

Male Sexuality and Extramarital Relationships

The dominant construction of women as the morality and family keepers and as sexually inferior is complementary and necessary to the construction of men as familially disconnected and sexually superior breadwinners. This complimentarity hinges on the Vietnamese binary view of Yin and Yang, two different parts that create a harmony. In other words, men and women have to be different; they cannot be the same and equal in order to have harmony. Jamieson comments that:

Yang is defined by a tendency toward male dominance, high redundancy, low entropy, complex and rigid hierarchy, competition, and strict orthodoxy focused on rules for behavior based on social roles. Yin is defined by a tendency toward greater egalitarianism and flexibility, more female participation, mechanisms to dampen competition and conflict, high entropy, low redundancy, and more emphasis on feeling, empathy, and spontaneity. (Jamieson, 12-13).

Vietnamese men believe that sexuality is one indicator of masculinity as they assume that they have the blood of the goat, and that the wife could not satisfy their sexual needs, so they have to engage in extramarital relationships, particularly with sex workers (who are believed to be different from other women in terms of sexual ability). While more respondents, regardless of gender, said the wife is not obligated to have sex with the husband than said she is obligated, the response to the sexual obligation of the husband is different. More than half of female respondents said the husband is not obligated to have sex with the wife, but half of male respondents said the husband is obligated (the statistic is significant at the 0.005 level) This data shows that sexuality is an important component of masculinity.

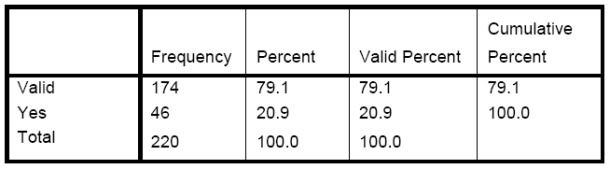

Sexual drives also become one of the reasons respondents used for extramarital relationships of the husbands. 20.9% of respondents agreed that a husband could have a sweetheart and 30.5% agree that a husband could seek sex workers because of his sexual needs.

Table 6: Husband having a sweetheart - Desire/need

Table 7: Husband seeking a sex worker - Desire/need

The construction of masculinity based on sexuality is so strong that this construction becomes quite homogeneous: gender, economic condition, education level, and age do not have significant relationships with the ideology about extramarital relationships. The only significant variation is along the urban/rural line. More men in rural areas said it is acceptable for men to have extramarital relationships than those in urban areas 31% of rural men indicated it was acceptable to have a sweetheart if the wife did not provide satisfying sex versus 18.8% of the urban respondents, while 49.1% of rural men approved of using a prostitute versus 29.2%. of the urban respondents under the same circumstances. This data is interesting given that when a man refuses to go to seek sex workers, his friends label him “countrified” or “rural” (nha que). Ironically, while men engage in extramarital sex to become “sophisticated” and “urban,” it is the rural men that may practice it more.

Sexuality is one of the main components of a Vietnamese “real” man, though it is less important for married men (who have their sexuality confirmed by their marriage and children) than unmarried men. Therefore, going to seek sex workers is considered as the rite of passage: married men will take unmarried men to houses of prostitution to initiate the transformation to be real men (Family Health International (FHI)’s Working Paper, 2006). It is also about male groups: men going together for bonding and to keep places in the social network, after doing business with colleagues, or as a “bribe” for bosses. Men also report going together so that they would feel less guilty (FHI). Ninety five percent of respondents said that they went to sex workers with other men and that their male friends know about their ventures but no one tells another’s wife.

The study by Family Health International shows that there are four types of men’s groups: playmates (ban choi), business colleagues and partners, bosses, and friends who are not playmates. When men go to sex workers, 90% of the times they go with playmates, 8 % with business colleagues, 2% with bosses, and never with acquaintances (FHI). This means that going to sex workers is usually a group activity and if one is not in a group, one rarely indulges.

Men have different attitudes about venturing out together. Some blame peer pressure because it is bizarre to break away from the group. Many others say it is peer encouragement more than peer pressure, because they all want to go to sex workers already and just need a little encouragement from friends. On the other end of the scale, some men also draw on the male “nature” of a strong sex drive to say it is the matter of saying no to oneself, because if one does not go, no one is going to force him (FHI). The reasons for engaging in extramarital relationships vary from adventure, sexual needs, sustenance of jobs and social groups, proof of masculinity, or having a son, to marital problems. As the primary status of being the main breadwinner is becoming difficult, women are demanding men to help out more in the family. The resistance of men means that more men may have extramarital relationships. But as the FHI study shows, even when men are satisfied with their marriage lives, many of them still have extramarital relationships. The conflicting attitudes and reasons demonstrate a strong masculine ideology: strong sexual desires (blood of the goat), bonding with other men, and family distance.

When a man refuses to go with other men to sex workers, he is judged as cheap, scared of his wife, weak (in sexuality), chicken (coward), countrified (old-fashioned). The real man, then, must be rich or generous, authoritarian over wife, strong in sexuality, fearless, and modern (which mirrors industrialization and urbanization). Vietnamese culture shows a binary view about masculinity and femininity. For example, a female name is normally a kind of flower or fruit, moon, charming, jewelry, while a male name is a king, dragon, strength, or big tree. In other words, a woman should be beautiful, sweet, charming, and gentle, while a man should be strong and powerful. If a man is not masculine enough, he is said to have the mix of both a man and a woman. He will be considered to have “eight lives” (tam via) since a man is believed to have seven lives and woman has nine lives, “gasoline mixed with oil” (xang pha nhot), hi-fi (“hi” is pronounced similar to number two in Vietnamese, so hi-fi refers to the mixed of two different things), a hen (as opposed to a cock), or pe-de which, though originally coming from the French word pede, a short form of pederasty (boy lover), means homosexual. By calling an unmanly man a homosexual, the Vietnamese also imply that a gay man is not a real man, invoking the definition of a real man: being strong sexually with women:

“A real man is the one that feels desirous when looking at women, wants to see women that are scantily clad, and dream of women’s bodies.” (Male, 29, Ho Chi Minh City)

The double standard in the construction of masculinity and femininity regarding sexuality (a real man has a high sex drive and a proper woman has a low sex drive) suggests that a homosexual man is a feminine man, and a sex worker is a masculine woman. Some Vietnamese men admire other men who have a lot of extramarital relationships (dao hoa) since “every man wants to be with many hot women, to be followed by women” (Male, 36, Ho Chi Minh City). A man who has relationships with many women is often depicted by other men as rich, gallant, chivalrous or as a playboy (silk-stocking). Such a man is considered admirable.

Interviewees reinforced the double standard in sexuality for men and women. While 91% of male respondents thought it is very important for the wives to be faithful, the corresponding number for husbands is only 67.7%. At the same time, fewer women require the husbands to be completely faithful than require the wives (80% as opposed to 94%).

It can be concluded that sexuality and extramarital relationships are strongly emphasized in Vietnamese culture as a component of masculinity. However, there is some resistance from both Vietnamese men and women. Some men have never had any extramarital relationships and refuse to go to sex workers when asked by friends. They come up with excuses, such as physically tired, too drunk, not in the mood, or having to go home to have sex with wives (to do “homework” – “tra bai”). The wives have their own prevention strategies: have sex with the husbands before they go out or calling them at pre¬determined times (FHI). But it is also notable that those who have never had extramarital relationships are not sure how long they can maintain their behaviors.

Given that the pressure on sexuality of men is so strong, and the double standard for men and women still exists, changes will be slow to happen. One of the factors that may contribute to changes is the concern with AIDS. The survey shows that a relationship with a sweetheart is believed to not bring a risk of disease. Having sex with sex workers is more risky, but only 17.6% of male respondents worry of AIDS while 42.9% of female respondents do (the statistic is significant at 0.005 level).

Although men go to sex workers in groups, they do not feel responsible if their friends get infected because the choice to go to sex workers is voluntary and each one is responsible for protecting himself (FHI). And although the risks are widely understood by both men and women, their perception of how the disease is transmitted is limited partly because of the taboos and the stigmas of “social evils” (FHI). Some men do not use condoms when having sex with other partners because of the belief in a “good” man: if one is a “good” man, he will be protected by Heaven’s will. Most of men do not use condoms in relationships with girlfriends, sweethearts, or small wives, which is highly risky. Vietnamese women report that they have no power in negotiating with their husbands about using condoms. According to the Family Health International’s report, some women choose to give their husbands condoms when they go out for the evening with friends.

In summary, the construction of masculinity and femininity in Vietnam is closely linked to sexual control and extramarital relationships. The ideals of women as family keepers, morality keepers, and sexual inferiors are paired with the ideals of men as distant breadwinners and sexual superiors. These ideals about women allow for the social acceptance of men’s extramarital relationships and social condemnation of women’s extramarital relationships.

Ironically for Vietnamese women, despite a long history of heroic behavior in wars, successful household economic activity, gains in education, and participation in the industrialized and commercial economy, they are still subject to gender subordination in public and in private. Jamieson states that:

The role of women was a source of tension in society. There was often a grating disjuncture between ideological ideals and sociological reality. Vietnamese myth, legend, and history are filled with stories of strong, intelligent, and decisive women. In all but the uppermost strata of society, men and women often worked side by side…yet ideologically men were yang; women, yin. Women were subordinate to men in the nature of things (Jamieson, 18).

The disjuncture persists today, between ideological ideals and sociological reality. There has been some resistance so that there are men and women who express other models of masculinity and femininity. Yet, the resistance is quite weak and will take a long time before substantial changes can be seen. As the economic sector expands, and women’s participation increases but they are blocked from achieving what men can achieve, the experience and frustrations of significant contradictions may lead women to seek additional political and legal reforms. Under current laws, women are forced to retire at 55, five years earlier than men. Women often delay their careers to bear and raise children. In addition, men in similar job positions often receive promotions and pay increases more and faster than their women colleagues. As a result, all sorts of social strains are likely to continue and to intensify in the future, at work and at home. Women’s increased participation and expanded role in the Vietnamese economy is a certainty. Yarr recognized this as early as 1966, pointing out that,

The need for women to obtain fair compensation for their labour is all the more critical since they are clustered in the very sectors of the economy that are most likely to expand as Vietnam increases its engagement with the global economy” (Yarr in Barry,114).

This has come to pass. At this point there certainly is an increasing disjuncture between the public and private spheres. Whether these social strains will resolve in the reduction of male privilege and a change in male marital and extramarital behavior remains to be seen.

Conclusion

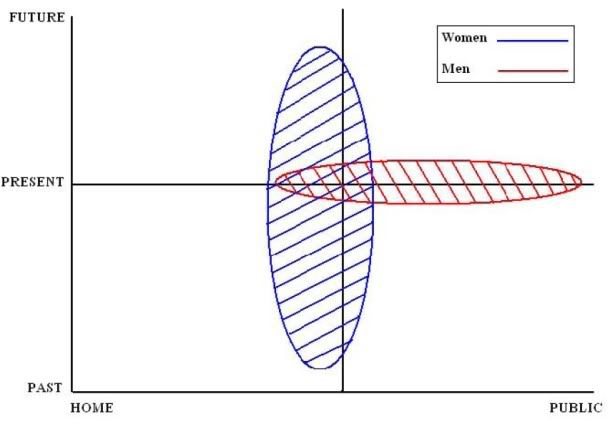

Heavily influenced by the ideology of Yin and Yang, Vietnamese masculinity and femininity are culturally constructed as inherently different but complementary. The women are caregivers, creating stability and harmony through their female networks. They are traditionally confined to households and small business economies within the villages. They are also constrained by the ideology of karma and merits (phuc duc), saving merits for generations to come. In other words, borrowing the concept of “integry” from Boulding (1980), Vietnamese women, working in their small female networks (space), are the glue among generations (time) to create stable families, the essential foundation and support of Vietnamese life. In other words, women in the past have often been restricted in their domains, primarily the household, the paddy, and the village market, and the public spaces dominated by men are not frequented by women.

Vietnamese men, on the contrary, are not the glue, do not need to save up merits, and are distant family breadwinners. They spend more time working outside of home, engaging in social interaction at the bia hoi (beer hall), café, or karaoke with their male friends, and they may also engage in extramarital relationships. They have little responsibility for critical matters of the past and future, which would include caretaking of the old and the young. Relating to all the Vietnamese analogies between extramarital relationships and eating, it is not stretching to say that a Vietnamese man spends his life moving in spaces out of home and “eating out.” This present orientation of a Vietnamese man is distinct and contrary to the generational responsibilities of a Vietnamese woman. The lives of Vietnamese men and women can be illustrated as followed: